The resolution of noise and speech privacy problems has proven elusive for many healthcare facilities, likely due to a fairly common misunderstanding of the mechanics of acoustics.

Most people are familiar with using walls, doors and a well-planned layout to block noise, as well as ceiling tiles, wall panels and soft flooring to absorb it. They know that these strategies are essential to achieving an effective acoustic environment, as are behavioral policies aimed at reducing noise

However, what many do not realize is that while these methods diminish volume peaks, they also decrease the overall background sound level in the facility. The lower ambient level actually makes remaining noises more noticeable and more disruptive. It is also easier for occupants to overhear conversations, even those occurring at a distance or in another room.

For some professions, having a conversation overheard is merely embarrassing, but in healthcare, it is a matter of confidentiality. That is why resources such as the FGI Guidelines for Design and Construction of Health Care Facilities now recommend the use of sound-masking systems to replenish and control ambient levels in healthcare environments, including hospital patient rooms.

Sound-masking technology consists of a series of loudspeakers, which are usually installed in a grid-like pattern in or above the ceiling, as well as a method of controlling their zoning and output. The loudspeakers distribute a comfortable, engineered sound that most people compare to softly blowing air. This sound completely covers noises that are lower in volume and diminishes the disruptive impact of those that are higher. It also greatly improves speech privacy.

Grady Memorial Hospital

Field tests performed on the fifth floor of the B-Wing at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta, Georgia demonstrate sound masking’s impact.

To begin, the existing background sound levels were measured in four rooms and a corridor. In three of the four rooms, ambient levels ranged from 39.3 to 42.9 dBA, which is typical of the low levels found in most facilities. Room 5B43 measured significantly higher (47.1 dBA) due to HVAC noise; however, the majority of this additional volume was focused in the lower frequencies, which do not contribute significantly to speech privacy or to covering noises in the higher frequencies.

Next, sound masking was tested in two rooms and adjusted to a 48 dBA target masking curve. The resulting masking sound conformed well to the target curve, in contrast to the levels without masking.

Finally, in order to quantify the intelligibility of speech, Articulation Index (AI) testing was performed in and around Room 5B42 and then translated into a ‘percent of sentences understood’ metric to better indicate subjective comprehension levels.

The first set of tests quantified how well a patient in bed could understand a conversation coming from the corridor. With the existing ambient conditions, the patient could clearly have understood conversations occurring more than 40 feet down the corridor, with 62 percent comprehension. When the masking sound was introduced, the level of intelligibility dropped sharply. For example, for a conversation occurring 10 feet from patient’s door, comprehension dropped from 97.5 percent to just 52 percent. Intelligibility dropped to just 22 percent at 20 feet and to nearly zero at 30 feet and beyond.

The second set of tests showed a similar pattern. In this case, testing was conducted to indicate how well someone in the corridor could understand a conversation coming from the patient’s room. Without the masking, comprehension remained at 85 percent and above, even 50 feet away from the patient’s door. With masking, comprehension fell quickly to 52 percent at 20 feet and just 5 percent at 50 feet.

Intelligibility between rooms across the corridor was also tested. Comprehension dropped from 92 percent without masking to just 25 percent with masking (in this case, at 47 dBA).

From this case study, sound masking’s measureable effect on speech intelligibility is clear. Subjectively, occupants would notice the reduction in comprehension as discussions occurred further away. At a closer distance, they would still hear that someone is speaking, but the conversation would be more private and much less disruptive. In this way, the technology not only helps to reduce noise, but also assists with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliance.

The masking sound would also create more generally comfortable acoustical conditions by reducing the quantity and severity of volume changes within the space. This ability to decrease the magnitude of change between baseline and peak volumes also has a positive impact on patients’ ability to sleep, as shown in the Stachina et al. (2005) study of ICU patients.

Niklas Moeller is the vice-president of K.R. Moeller Associates Ltd., a global developer and manufacturer of sound masking system, LogiSon Acoustic Network (www.logison.com). He also writes a weekly acoustics blog called “UnMasked – an inside look at acoustics.”

Building Sustainable Healthcare for an Aging Population

Building Sustainable Healthcare for an Aging Population Froedtert ThedaCare Announces Opening of ThedaCare Medical Center-Oshkosh

Froedtert ThedaCare Announces Opening of ThedaCare Medical Center-Oshkosh Touchmark Acquires The Hacienda at Georgetown Senior Living Facility

Touchmark Acquires The Hacienda at Georgetown Senior Living Facility Contaminants Under Foot: A Closer Look at Patient Room Floors

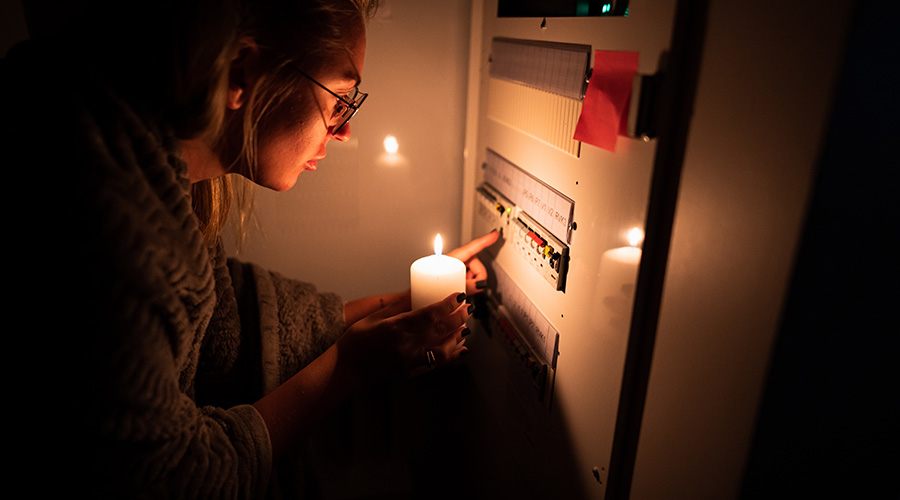

Contaminants Under Foot: A Closer Look at Patient Room Floors Power Outages Largely Driven by Extreme Weather Events

Power Outages Largely Driven by Extreme Weather Events