Hand hygiene is a cornerstone of infection prevention in healthcare facilities as it’s simple and effective. However, ensuring consistent adherence among healthcare workers is challenging, and monitoring compliance requires a significant investment of time and resources.

A recent study published in the American Journal of Infection Control (AJIC) looks at whether hospitals can achieve statistically reliable hand hygiene compliance data with less observations. The research, led by Sara Reese, director of research at APIC’s Center for Research, Practice & Innovation, found that reducing hand hygiene observations from the current standard of 200 per unit per month to 50 could free up substantial resources without compromising data integrity.

Healthcare Facilities Today recently spoke with Reese about the implications of her team’s findings, how they could affect infection prevention efforts and what this could mean for healthcare facilities trying to balance monitoring requirements with broader infection prevention initiatives.

HFT: What motivated you and your team to investigate reducing the number of hand hygiene (HH) observations required in hospitals? Was there a particular challenge or gap in the current system that you aimed to address?

Sara Reese: As an infection preventionist (IP) that works in a hospital, the current ask is 100 to 200 observations per unit per month. It’s very lofty and time consuming. It’s also very difficult to get that number of observations. So, in my current role as director of research for APIC, we’ve had numerous hospitals coming to us and asking us to investigate if that was something that could be changed or influenced. Could there be some data found to support the idea that a number this high isn’t going to be adequate? Maybe we could do a lower number and have it be more comparable statistically?

Either through people just being unhappy with the current system or experiencing ourselves as IPs in these facilities, we ultimately decide the goal would be to have enough data to influence Leapfrog to change their current standards of reporting. The change would be to just 50 observations so more attention can be focused on the other aspects of building a culture of safety rather than targeting a specific number in each unit per month.

HFT: Your study found that reducing observations to 50 per unit per month provides statistically comparable results to 200 observations. Can you elaborate on how this finding could impact infection prevention efforts in healthcare facilities?

Reese: So, the number of resources that are currently dedicated to collecting the current requirement of 100 to 200 is tremendous between training staff to collect the data that are on the units or putting that responsibility solely on an IP. If you have a hospital with up to 15 to 20 units, that’s a huge time sink. By reducing the number to 50, the IPs can more likely collect the data themselves, which improves the data integrity and makes sure you have accurate data.

Just having a lower number of observations for the staff that collect it that are on the unit would free up time to do other infection prevention activities. It would also allow IPs to focus their efforts on preventing infections rather than just collecting hand hygiene observation data just to meet the standards. I’ll also add that if Leapfrog can put more weight on building a culture of safety around education, training and transparency with the data and less on number of observations collected, ultimately that’s going to improve your infection prevention practice.

HFT: The study highlights significant cost and time savings from reducing HH observation requirements. How do you envision hospitals reallocating these resources to enhance hand hygiene practices and patient safety initiatives?

Reese: I think you’re just putting more resources back into the infection prevention team. I doubt anyone would go this route, but it’d be really nice to be able to instead of dedicating $50,000 to $60,000 to collecting this many observations, give it to an IP team and others. Really, just those resources could go into infection prevention activity initiatives to help support the infection prevention efforts rather than collecting a certain number of observations each month.

Related: Healthcare Facilities May Reduce Amount of Hand Observations

HFT: Hand hygiene adherence remains a challenge in healthcare. Beyond reducing the number of observations, what additional steps do you believe are necessary to foster a culture of compliance among healthcare workers?

Reese: I feel like for IPs and healthcare workers across the board within a hospital, it really needs to come down to what’s the reason behind collecting these observations? Why is it important to make sure people are washing their hands? You’re going to save lives.

It comes down to more of it not being complying with doing something because we ask you to, but the importance of washing your hands because you don’t want to transmit something from one patient to another. That’s the culture we need to build, and once you build that culture and the expectation that you’re washing your hands to protect patients, that’s going to make a difference.

Rather than we saw you didn’t wash your hands and make it more of a compliance issue. Instead, it’s more of a general understanding of the importance of hand hygiene, what that does for your patients and the overall culture of your organization.

HFT: What are your recommendations for organizations like the Leapfrog Group or other accrediting bodies in light of your findings? How quickly do you think these standards could be revised to reflect the study’s conclusions?

Reese: My recommendation would be to put less weight on collecting a specific number of observations to determine your hand hygiene compliance. There’s a lot of challenges with direct observations and with electronic observations. Ultimately, your data integrity suffers when you just put an emphasis on collecting a number each month.

Also, it comes down to what hospitals and infection prevention programs can do to show they’re doing more with training and education around patient safety and prevention initiatives. That is, rather than focusing on the fact they collected 200 observations in their ICU that month.

As for the impact for organizations to take the recommendations from our paper, that is yet to be seen. Though, Leapfrog has just recently asked for comments on their 2025 survey. We also provided the citation for the paper, and they know our recommendations. So, I think there’s a lot more conversation around it and it would be great if we could see a change within the next year.

Jeff Wardon, Jr., is the assistant editor for the facilities market.

Building Sustainable Healthcare for an Aging Population

Building Sustainable Healthcare for an Aging Population Froedtert ThedaCare Announces Opening of ThedaCare Medical Center-Oshkosh

Froedtert ThedaCare Announces Opening of ThedaCare Medical Center-Oshkosh Touchmark Acquires The Hacienda at Georgetown Senior Living Facility

Touchmark Acquires The Hacienda at Georgetown Senior Living Facility Contaminants Under Foot: A Closer Look at Patient Room Floors

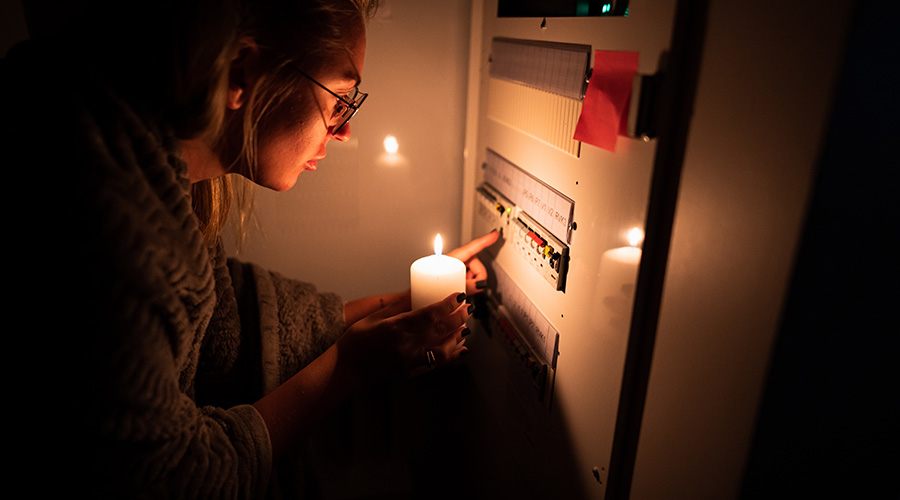

Contaminants Under Foot: A Closer Look at Patient Room Floors Power Outages Largely Driven by Extreme Weather Events

Power Outages Largely Driven by Extreme Weather Events