When two healthcare workers in Texas became infected with Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) in 2014 after treating a patient with the disease, their diagnoses prompted concerns about America’s readiness to cope with the dangerous pathogen.

Although the patient passed away, the two workers did recover. In part, that’s because the professionals involved in their treatment have learned a great deal about creating environments that allow for the safe treatment of patients with EVD and other infectious diseases.

Communication is a critical starting point. “The key to any risk mitigation in healthcare is transparent, interdisciplinary communication,” said John D’Angelo, vice president, facilities with Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill.

In his previous position as vice president of engineering and facilities operations with Manhattan’s New York-Presbyterian Hospital, D’Angelo oversaw the design and construction of a suite for patients with EVD.

With EVD and other highly infectious diseases, the roster of departments that should be part of any communications is lengthy. Among others, it can include physicians, nurses, facilities, supply chain, infection control, administration, clinical engineers, staffing, waste management, IT, communications, and the emergency care.

“This is an institution-wide response,” said Brian Garibaldi, M.D., Garibaldi was recently appointed the Associate Medical Director of the newly formed Johns Hopkins Biocontainment and Treatment Unit. Johns Hopkins is one of the CDC designated Ebola Treatment Centers. Garibaldi is also a fellow in pulmonary and critical care medicine at Johns Hopkins Medicine.

Another key to successfully equipping a facility to treat patients with infectious diseases is walking through all the steps that will occur — before they happen in real life. “Have a plan,” said Michael Iati, senior director of architecture and planning with Johns Hopkins Health Systems. “Ask, ‘How will you transport the patient? Where to? What’s the best route? What’s the number of people involved? Will the equipment fit in the elevator?’”

Iati likened the approach to that required in any facility that requires a great deal of training and a well-documented process, such as a high-level research lab or space ship. In fact, he recommends thinking of the communicable disease unit as being hundreds of miles away from the rest of the facility, given how isolated it will need to be.

D’Angelo said that while actually building the Ebola suite required a great team effort, the critical piece was the planning and preparing that occurred before a single hammer started pounding. He and the others involved in the planning had to think through exactly how patients, the care team, and medical equipment and supplies would flow from other parts of the hospital to the suite.

Once the plans were in place, the actual build out was done over a weekend. Several teams took turns on the job, so the work could continue 24/7, D’Angelo said. Observers were on site to watch for signs of fatigue that could lead to mistakes.

Disease transmission

Facilities professionals also need to gain an understanding of how diseases like EVD are transmitted and the tools available to help contain them, said Leonard Taylor, senior vice president, operations and support services with the University of Maryland Medical Center/Systems in Baltimore. For instance, the settings of a facility’s temperature, humidity and static pressure can impact the ability of an infection to spread.

“Anyone working in hospital facilities should have a good working relationship with the infection prevention team,” he added.

While the Ebola virus generally is believed to be transmitted through bodily fluids (although some infectious disease experts say it’s not possible to rule out the possibility of airborne infection), patients with advanced cases of the disease can exude fluid from just about every orifice, Taylor said. As a result, healthcare workers need to be in full protective suits. The rooms in which they work need to be large enough to accommodate the gear.

Treatment area location

A key principle in treating patients suspected of carrying infectious diseases is isolating them as soon as it’s determined they may carry a pathogen, Iati said. Deciding on the location of the isolation area often means weighing competing interests. It should be as isolated from the rest of the facility as possible, yet also readily accessible from the outside, as that minimizes the length the patient has to travel through the hospital, potentially putting other staff and patients at risk.

“You want a discreet location that’s easily sequestered from the rest of the hospital, but still reasonably accessible for the patient, supplies, and (the removal of) waste,” Iati said.

Access control

Reducing the risk of transmitting an infectious pathogen to those outside an isolation unit requires limiting the number of people who have access to the unit. Security and access control are essential.

That may mean food service employees don’t enter the isolation area, but instead ring a doorbell and leave the food just outside the door. Similarly, family members often interact with patients via telecommunications systems, Garibaldi said. As difficult as this may be for all involved, it is crucial in controlling exposure to harmful and deadly diseases.

Limiting the numbers of people with access to an isolation area offers other benefits. If a problem arises happens and it becomes necessary to follow up with those who’ve been in the area, the job is more manageable, Taylor said. It also limits the likelihood a serious healthcare situation will turn into a circus, he added.

Size requirements

The areas for treating patients with infectious diseases often must be larger and have access to greater levels of electric power than other patient rooms. To start, the personal protective gear healthcare workers must wear is bulky. They need more space just to do their jobs.

Not only that, but the care teams often include several groups of people who aren’t needed with most other patients. One example: individuals who help healthcare workers safely don and doff their protective gear. Another is observers who ensure those working with a patient don’t inadvertently overlook any steps that could put them at risk.

The result? An isolation patient room can be twice the size of a regular patient room.

Moreover, it often makes sense to locate laboratory or diagnostic equipment within the isolation area, as this limits the need to move potentially dangerous samples to a lab, which could increase the chance of contamination. The University of Maryland, for instance, assembled a small, full service lab within its bio-containment area, Taylor said.

Flow of air and work

With airborne infectious diseases, it’s not enough to simply isolate a space, Garibaldi notes. The dangerous pathogens also need to be contained. One way to accomplish this is by keeping air pressure in the patient rooms lower than in adjacent rooms. That way, clean air flows one way: into the room. From there it typically passes through a HEPA (high-efficiency particulate arrestance filter) before flowing outside the building.

The air pressure in the patient room at New York-Presbyterian was lower, or negative, to both an anteroom from which healthcare workers entered, as well as to the “doffing” room, where workers removed their protective gear after spending time with a patient, D’Angelo said. This way, the flow of both workers and air went from clean to dirty in a clockwise pattern, reducing the risk of contaminating the clean air and space.

Waste handling

While safely handling and disposing of waste is a concern in any healthcare facility, it becomes even more important — and challenging — when dealing with the Ebola virus. Ebola waste is “a Category A infectious substance regulated as a hazardous material,” according to the Centers for Disease Control. It’s subject to a host of regulations governing how it’s treated and transported.

The disposal process can require a number of steps. At Johns Hopkins, for instance, the waste is bagged, and the bag wiped with disinfectant. It’s bagged again, and then auto-claved, or sterilized through the use of steam. It’s then encased in drums and transported as medical waste. In addition, workers must record every batch of waste leaving a bio-containment unit, Iati said.

Once Ebola-associated waste has been auto-claved or otherwise inactivated, it’s no longer considered a Category A infectious substance, the CDC said, although it still is subject to disposal regulations.

FMEA

When designing, operating and maintaining a space for treating patients with serious infectious diseases, it’s critical to apply the principles of FMEA, or failure mode effects analysis, Taylor said. That is, you want to methodically identify all possible failures in the process.

“You have to ask, ‘What can go wrong? How can we error-proof the process?’” Taylor said. The group charged with putting together the plan should include people who aren’t afraid to point out potential problems and glitches. “The people around who see the bad — that’s who you want on your team.”

“Ebola made people realize we need to improve our ability to respond to highly infectious pathogens,” Garibaldi said.

Building Sustainable Healthcare for an Aging Population

Building Sustainable Healthcare for an Aging Population Froedtert ThedaCare Announces Opening of ThedaCare Medical Center-Oshkosh

Froedtert ThedaCare Announces Opening of ThedaCare Medical Center-Oshkosh Touchmark Acquires The Hacienda at Georgetown Senior Living Facility

Touchmark Acquires The Hacienda at Georgetown Senior Living Facility Contaminants Under Foot: A Closer Look at Patient Room Floors

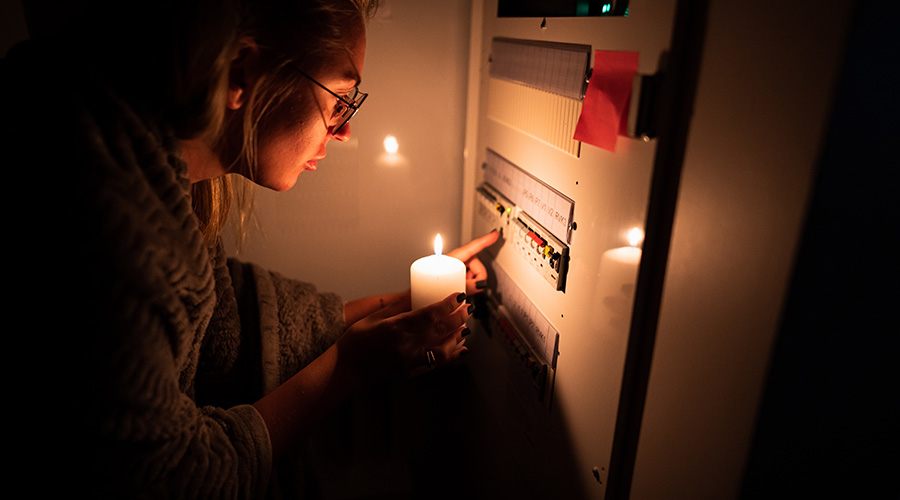

Contaminants Under Foot: A Closer Look at Patient Room Floors Power Outages Largely Driven by Extreme Weather Events

Power Outages Largely Driven by Extreme Weather Events