Sustainability and resiliency are common buzzwords today. But for healthcare facilities to make progress in these areas, it’s important to take a practical, feasible approach that aligns with budget considerations. Thinking strategically about incorporating sustainability can help hospitals save resources and become more efficient.

Sustainability in healthcare

Sustainability requires evaluating systems — including building infrastructure and organizational practices—and implementing measures in line with proper budget planning. A healthcare facility needs to have reliable and resilient engineering systems to ensure safety for its patients. While other industries may be more willing to try new technologies and strategies to promote sustainability, healthcare facilities must find solutions proven to work in the unique health care environment. A strategic approach to health care sustainability can incorporate factors such as limited funding, the rigorous facility accreditation processes, and a low risk tolerance.

Understanding budget priorities

Ninety-nine percent of large hospitals have regular HVAC maintenance and repair scheduled, Feature according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s Commercial Building Energy Consumption Survey (CBECS). Scheduling preventive maintenance is a good first step in addressing resiliency and sustainability. Unfortunately, since preventative maintenance takes consistent funding to keep up with the annual stream of preventive maintenance tasks, funding isn’t always available for additional sustainability initiatives. The operations and maintenance budget is often a target for cuts, which makes funding an additional challenge.

Limits in funding are often reflected in facility conditions. When the choice is between maintaining the reliability of the existing systems and implementing new programs to achieve sustainable objectives, facilities will often opt to fund maintenance. A commonly cited general figure is that every $1 invested in preventive maintenance avoids $4 in future repairs. The return is considerably better in healthcare when factoring the costs of unexpected downtime. For example, the loss in revenue from a patient room requiring maintenance ranges from $3,000 to $13,000 per day.

To achieve funding for sustainability initiatives, it’s important to make a solid business case. As in any organization, business decisions in healthcare are made based on the health and growth plan of the organization. To grow, organizations must increase annual revenue and deliver services with sufficient margin (profit). Saving energy leads to savings, and ENERGY STAR® neatly summarizes the impact of energy cost savings on the financial health of hospitals:

• One dollar saved from energy conservation is approximately $20 in new revenue for hospitals, based on a typical 5 percent profit margin. • Assuming a 20 percent annual energy savings, implementing a $100,000 energy conservation project (and reaping $20,000 in savings) would be the equivalent of generating $400,000 in new revenue per year (for the life of the improvement).

Challenges

Facility professionals care about their buildings and take pride in their systems, just like nurses care about their patients.

Facility staff are in a state of triage — stabilizing systems to remain operational and regularly appealing for funds, staff, and time to keep the facility at peak performance and competitive. However, as deferred maintenance grows, building systems can begin a downward spiral of breakdowns requiring emergency repairs, which cost more than preventive maintenance and subsequently divert resources from planned projects. Energy efficiency also may suffer, and ENERGY STAR® ratings can drop.

This process is complicated by staff turnover and an aging workforce. Buildings do not run on autopilot. Systems must be monitored and actively managed by people based on activities in the building and outside conditions (i.e., weather). Documenting operating practices is a good start, but ultimately the facility staff needs to have a succession plan that shares knowledge and cultivates the next generation.

Further, hospitals are constantly in a state of upgrade, modification, change, or expansion. Because of the constantly evolving state of health care, facilities often change the use of space and add equipment without truly considering the cumulative effects of small changes on building infrastructure and operations. Frequently, projects are completed by one group of facility staff, but maintained by another division. Without productive communication, installed equipment and even patient safety and satisfaction improvements may be counterproductive to the building’s central plant — or worse, completely unknown to the operations and maintenance staff. In healthcare organizations, facility staff is in the prime position to identify, develop, and implement projects and practices that advance sustainability. But this requires leadership and investment.

Strategic energy planning

Reducing energy use in healthcare facilities savings money, but it also can improve health and support better patient experiences.

Strategic energy planning aligns well with healthcare’s Triple Aim:

• Improve population health

• Improve the patient experience

• Reduce per capita cost

Strategic energy planning involves making a comprehensive evaluation of the organization’s current energy needs, forecasting future energy needs, and identifying strategies to include in operations budgets and capital planning.

An excellent starting point for operational sustainability in healthcare is an evaluation of existing systems and equipment. In a 40-year-old hospital, the following conditions may occur:

• Major equipment has reached end-oflife and needs to be replaced.

• The hospital has been periodically investing in new equipment with improved efficiency ratings, but the facility has a low ENERGY STAR rating.

• Through good preventive maintenance practices, major equipment is in good condition, but parts are difficult to find and distribution systems are failing.

Facility staff must have a comprehensive understanding of the condition of building systems and equipment. This understanding should include the following:

• A list of all major equipment, indicating the condition of the equipment (i.e., good, bad, critical), including critical points in distribution systems

• A technical narrative of building operations under typical conditions

• An analysis of risks and vulnerabilities resulting from building systems and equipment

• The cost estimate to replace or fix bad and critical conditions

Once facility staff has a thorough documentation of existing infrastructure, leadership can create a multiyear plan to address and correct the deficiencies and incorporate these projects into strategic energy planning.

Developing an energy management program will help optimize a facility. A program that analyzes actual building performance data (not just kWh, but also temperatures, schedules, and sequences) can help facilities reduce energy consumption, provide a healthy indoor environment, and identify potential maintenance issues before they become critical.

Retrocommissioning can help hospitals find low-hanging fruit. Through the retrocommissioning process, the building is evaluated to optimize performance using existing systems and equipment to meet current user requirements. This considers the current capabilities (capacities) of installed equipment and can be a good opportunity to review space temperature setpoints and operating schedules with occupants.

Much can be accomplished through trend analysis of the existing building automation system (BAS) to review system setpoints, operating schedules, and control sequences for HVAC. Trend data from the BAS also can identify malfunctioning controls, components that were not identified in the assessment of major equipment (i.e., frozen actuator, sensor calibration).

Reprogramming the controls workstation, replacing failed components, and cleaning and calibrating sensors are all strategies that require little cost to complete that can generate immediate energy savings and comfort improvements. Cumulatively, these quick fixes hold the potential to significantly reduce a facility’s annual energy costs.

Other opportunities, such as programming for chiller plant optimization, may have an even bigger effect on energy consumption. However, these may require more technical analysis, and implementation may require retrofits to the distribution system (i.e., reconfiguring piping configuration, adding VFDs to pumps/fan).

Additional opportunities likely exist with capital investments in new air handling units (AHUs) with energy recovery, ground source heat pumps, CHP/cogeneration, on-site renewable energy generation with solar photovoltaics, and green roofs. While these are viable investments for many facilities, each facility has a limited budget and should use their strategic energy plan to prioritize investments in energy efficiency for sustainability.

Showing return on investment

Financial savings from improved energy performance can be readily calculated using tools such as ENERGY STAR Portfolio Manager. This free tool from the EPA allows a hospital to compare its annual energy consumption to other hospitals and estimate cost savings from improvements.

With a few basic assumptions, we can extrapolate the estimated return on investment (ROI) as:

• Hospital annual energy costs: $3 per square foot

• Cost of energy improvements: $1.50 per square foot

• Annual energy savings: $0.60 per square foot, assuming a 20 percent improvement in energy efficiency

• Simple Payback: 2.5 years

• ROI: 40 percent

Operating cost savings from energy conservation can help facility professionals gain approval for projects. But ultimately, sustainability comes down to alignment with the mission of the organization, which can often be summed up as: 1) do no harm, and 2) heal.

Any changes to the facility should improve the indoor environment for patients and staff. A simple narrative to document these improvements can be used to communicate the benefits of these facility investments and generate goodwill in the community.

Further, studies have documented the costs to communities from energy consumption. For electricity consumption, the public health effects have been quantified on a cost per kWh basis, similar to utility bills. The associated health cost per kWh varies across the country, depending on how electricity is generated, from 50 percent to 500 percent of the utility cost of electricity. Therefore, as healthcare systems account for investments in community health, the avoided energy costs can also be leveraged to support public health.

Conclusion

Thinking strategically about sustainability and investing in energy efficiency can help hospitals reach their goals. Optimizing facility operations can help reduce operating costs, improving the patient experience, and promoting community health.

This article originally appeared in Inside ASHE. Copyright ASHE 2016, reprinted here with permission.

Reframing the Construction Manager as a Community Manager

Reframing the Construction Manager as a Community Manager Health First Celebrates 'Topping Off' Ceremony for New Cape Canaveral Hospital Campus

Health First Celebrates 'Topping Off' Ceremony for New Cape Canaveral Hospital Campus The University of Hawai'i Cancer Center Caught Up in Cyberattack

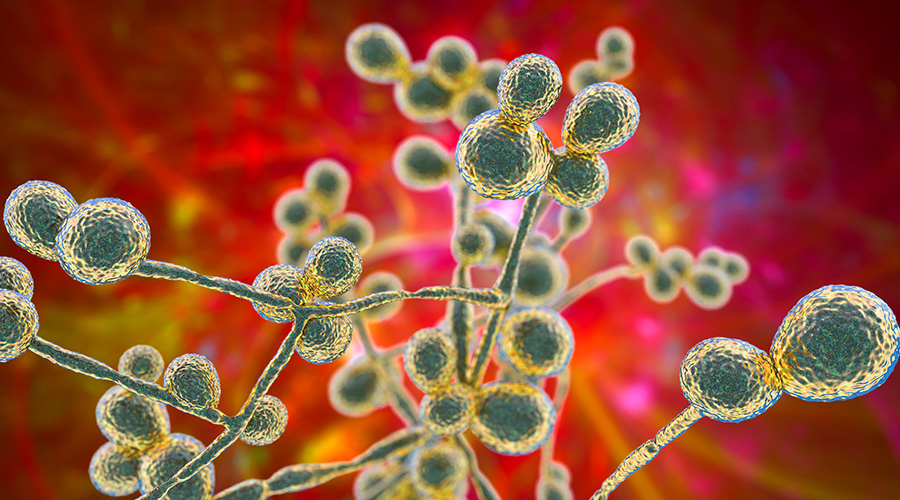

The University of Hawai'i Cancer Center Caught Up in Cyberattack Mature Dry Surface Biofilm Presents a Problem for Candida Auris

Mature Dry Surface Biofilm Presents a Problem for Candida Auris Sutter Health's Arden Care Center Officially Opens

Sutter Health's Arden Care Center Officially Opens